Last week, we launched ourselves back into Disney history to find the spark which ignited the Disney’s America project . . . and Part One of our roller coaster story began. This week, we find ourselves barreling toward a brand new theme park. Will all go as planned, or will the project be thrown for a loop?

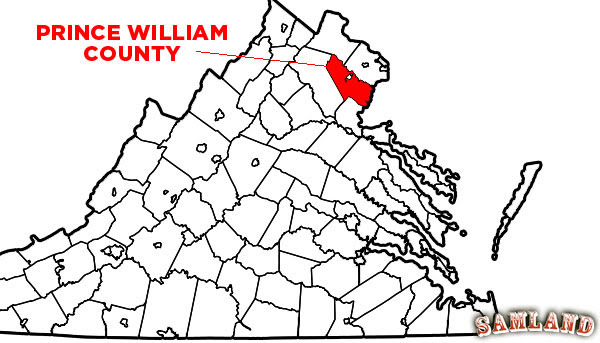

In 1993, Rummell found 2,300-acres in suburban Prince William County that was owned by the Exxon Corporation. During the hot real estate market of the 1980s, Exxon bought a lot of land and wanted to build a large mixed-use development with homes and office buildings. They went through a lot of trouble to obtain the necessary land use entitlements, which is a very costly and time-consuming process.

Prince William County had seen some tough times. During the 1980s, the population grew by 50 percent but business development did not keep pace. A development called the William Center was stopped and the land was sold to the federal government. In 1990, the County adopted a plan to lure 14,000 new jobs and $1 billion in nonresidential growth by 1997. They were very aggressive and advertised nationwide. The community even raised money through infrastructure bonds to support this initiative. Officials even courted Lego for a US theme park, which peaked Disney’s interest.

Disney has a long history of creating themed environments based on America’s past.

Disney’s America was going to be set on 3,000-acres in the rural rolling Virginia countryside. The project was going to be far more than just another theme park. In addition to the park, visitors would find a water park, 1,340 hotel rooms, a twenty-seven-hole public golf course, 300 campsites, and 1.3 million square feet of retail space including a new convention center, and 630,000 square feet of office/business space.Disney also wanted to sell part of the land to a developer to build 2,300 to 2,500 homes. The company planned to set aside land for schools and a library. The budget for the theme park alone was slated to be between $625 million to $650 million.The resort would take up 1,200 of the 3,000-acres with the balance (40%) going toward a greenbelt surrounding the project. This greenbelt would act as a buffer. As stated in one of the early press releases, Disney claimed that, “Disney’s America will be an example of our company’s commitment to creating communities that are unique in their design and execution and harmonious with their natural setting. It will incorporate numerous innovative ideas to protect and enhance the environmentally sensitive features of this beautiful site.” The press released suggested that “forest and wildlife corridors will be protected by several hundred acres of open space. Greenbelt and conversation buffers will ensure that we not only harmonize with the environment, but with our neighbors as well.”

Rummell recognized that there were a number of differences between the Disney proposal and the shopping center project. Disney’s park boundary was approximately four miles from the Manassas battlefield. Because, it was already zoned for residential use and the entitlements were already in place, everybody’s expectation was the property Disney had optioned was going to be developed at some point. Nobody was trying to preserve the land and no land conservancy was trying to purchase the property.

Disney knew that a lot of wealthy and powerful people lived west of the project in Loudoun and Fauquier Counties but the project was located in Prince William County and that county was slow to develop and needed the tax revenues. Disney thought that they would be more than welcome by local officials once they had acquired all of the property they needed.

The location had a number of other benefits. As a regional sized park, it would not compete for visitors with either Disneyland or Walt Disney World. With more than 19 million tourists visiting the area according to the National Park Service, the location near Haymarket Virginia looked perfect.

Rummell was confident and said, “We hired some local lawyers and did what we thought was a pretty good analysis of the potential competition. We were very methodical…very careful about the product we put together.” Michael Eisner added, “I thought we were doing good. I expected to be taken around on people’s shoulders.”

Then the local paper got word of the secret project. The problem was that the local paper happened to be the internationally famous and influential Washington Post and its publisher, Katherine Graham, just happened to live west of the project area in what is known as the Virginia hunt country. As Mark Twain observed, “Don’t pick a fight with anyone who buys ink by the barrel and paper by the ton.”

The headline in The Washington Post was SMOGGY, CLOGGY TRANSPORTATION MESS. Unfortunately, for Disney, this is how local county officials also learned about the project. Up until now, Disney did a great job of keeping the project a secret from everybody. The article featured pictures of the site with the caption “A Cinderella Story – Or a Bad Dream?” Another headline would read EEEEK! A MOUSE! STEP ON IT!

As one could imagine, this surprise did not sit well with local officials. Doug James, former director of planning for Prince William County said, “The next day when we went to work, there was all the buzz. From the beginning, we were curious as to why we were the last to know. The [Disney] response was, they had to acquire the lands very secretively in order to keep the price down.”

Once the word about the secret project was leaked in October 1993, Disney was forced to reveal more of its plans. A press release was sent out on November 11, 1993 that outlined what the company was trying to accomplish with this project. The project’s goal was “to create a unique and historically detailed environment celebrating the nation’s richness of diversity, spirit and innovation – “Disney’s America” – to be located west of Washington DC.”

Doug James described that first meeting between his staff and the Disney team. He said, “The Disney folks basically told us they wanted to have all their permits in hand, because they wanted to begin construction in six months.” In the end, the project would require as many as 11 separate related applications including changes to the zoning code, amending the comprehensive plan, and seeking variances in the building code and use permits. The project timeline called for all of the necessary entitlements to be completed by 1994, construction to begin by 1995, and the park opening in 1998.

Once the project became official, many public leaders in Prince William County voiced their support. Kathleen Seefeldt, chairman of the board of county supervisors said, “ economic development, is the number one goal” for the county. She added the Disney project should “exceed all reasonable expectations for economic development” in the near future.

Next week, we will take a closer look at the Disney’s America project details.

You must be logged in to post a comment.