Howdy everyone—in the past few weeks, I’ve been hearing a tremendous amount of commentary about the creation of successful portrait figures (that is, animatronic or static characters designed to look like a realistic, lifelike, or specific person). I’ve even been asked by a number of parties to give my opinion (as someone with a bit of working knowledge on the subject) about how and why some characters fail. It’s actually a topic I’ve thought about a lot in forty years of creating animatronics at my company, Garner Holt Productions, Inc. (GHP). For us, getting something right can often be the difference between getting paid for our work or not, and a reputation is often built or toppled by creating characters who look real or like their real-life counterparts (and we usually have the added challenge of making it look real while it’s moving).

A Human Experience

People have attempted artistic replication of the human form since the beginning of the artistic record. Highly stylized depictions on cave walls gave way to more detailed and lifelike representations in relief carvings in ancient Egypt, illustrations in illuminated manuscripts, and a sense of perfection in Greek and Roman sculpture and, later, during the Renaissance when the outer physical form began to be influenced by a growing knowledge of the interior anatomical structures of humans. From this information, the creation of much more lifelike dimensional representations of people was possible—it was now understood why people had certain features because of a knowledge of what was going on beneath the skin, not merely observing the effects of physiological structure. Even so, turning that knowledge of correct anatomy into a realistic dimensional portrait is an incredible challenge, particularly if the subject is a specific individual.

Imagine that of the more than seven billion people on the earth, no two have exactly the same face. In a physical structure on the body, something like the size of a melon, and a general surface about six inches wide and ten inches tall, the face can have enough subtle difference from one person to the next that the change in minute fractions of a millimeter can change an aspect enough to make it unique. Across families, even between twins, these subtle movements of pores, bumps, and structures major and minor can make it so that nobody looks precisely like anyone else. As a result, creating a physical sculptural representation of anyone is a wildly complex challenge.

As humans, we are so attuned to the subtleties of the face—its structure, fluidity for expression, familiarity among friends, family, and celebrities—that bad likenesses are perceptible from an unconscious level. Frequently, we can tell that something is wrong with a likeness, but not necessarily what is wrong. Observations like this are often subjective: between siblings, one may think a sculpture of their mother looks exactly like the real person while the other may think the resemblance is totally lacking.

Getting Started and What to Look For

Before we begin the work of creating a sculpture, we build a large library of reference material in the form of photographs, video clips, sometimes even other sculptures of the same subject. The more diverse the range of images—showing the subject from multiple angles, in different lighting and environments, even at different ages—the better chance we have of capturing a true likeness. Our best results come when we can actually digitally scan the subject as we have done many times to replicate a real, living person. Other times, we can sculpt a subject digitally and overlay images to match exactly the aspect given in certain poses. I’ve come to favor digital sculpture in recent years because of the ease of using techniques like this, and the ability to make large-scale changes without wasting materials.

Life or death masks pose an interesting challenge and a bit of deception as research tools. Obviously, they are probably the best dimensional representation of some historical figures available (think of the two Lincoln life masks, or the death masks of Beethoven, Napoleon, or Dante) but they are never to be trusted for accuracy and should be used only as a start (like Blaine Gibson’s superior Lincoln). Most life and death masks have significant gravitational distortion, signs of rigor mortis, or shrinkage in the plaster or other casting material. Sometimes such masks are most helpful in visualizing the basic structure of a face—cheek and chin positions and the like—rather than in use as an actual portrait.

Based on availability of research, some faces are just easier to nail. Abraham Lincoln, for instance, is both well known and has a finite number of images that make certain depictions of him seem inviolate and definitive, such as how he looks on a five dollar bill. As a result, getting a sculpt to look exactly like one particular image can help make the physical form stand for all images and therefore be a success. The sculpt is almost an expression of a collective experience of a person, more so than a realistic one (and we only know of Lincoln looking serious in portraits—his face would have looked rather different when telling one of his famous humorous stories). By the same token, a danger in this persists…you just can’t please everyone.

Looking at Things in the Right Light

One major element I’ve noticed in creating portrait sculptures is the importance of lighting during the process both of building and performance. People’s aspects can change enormously depending on the light. For instance, we’re used to seeing actors rather artistically and well-lit, and made-up, in film and TV roles. But if we were to see the same actor in the real world, under less flattering lighting in normal conditions, his or her face may appear rather different—the subtle differences in shadow and highlight lend a totally unique look to the face, sometimes to the point where the person may be nearly unrecognizable. In the same way, lighting in a show environment can totally wreck the care and work of a sculptor by not enhancing skin tones, or by flattening structure or causing unnatural shadows.

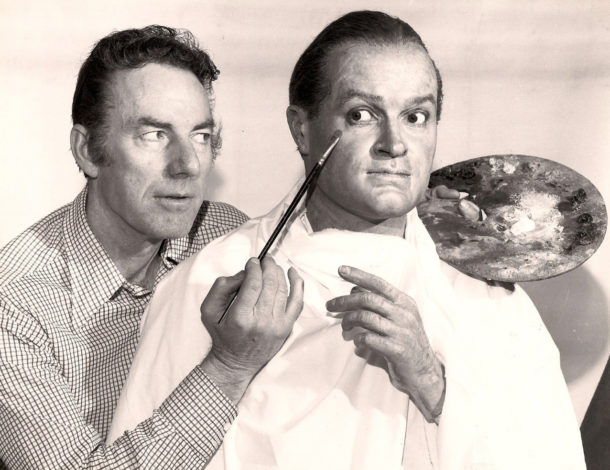

In some of the best wax museums, some celebrity likenesses are totally nailed and perfect, and others are just missing something. I think much of this has to do with lighting and the environment in which a character is sculpted. The famous sculptor Logan Fleming—who sculpted the majority of the heads of the figures at the much-lamented MovieLand Wax Museum in Buena Park, CA—used light (particularly theatrical show lighting) as a tool for his sculptures. As a prolific portrait and advertising painter, he knew color, light, and shadow could be used to define the structure of a face almost as much as the basic line of composition. When it came to working in dimensional media, he employed similar techniques in adding or enhancing structure with surface-applied paint. He took works in progress to the sets where they would eventually stand to observe them under the lighting conditions that would exist when guests saw the finished work. This allowed him to dial in structures of a face to their best effect in sculpture. Later, he did his painting under the same conditions of the real show lighting for the figure, adding shadows and highlights that could give the illusion of further refinement to a given sculpture.

Sticking Your Neck Out

The overall accuracy and effectiveness of a portrait figure can be severely undermined if the body is not properly scaled to the neck and head, and vice versa. The attachment of shoulders to neck at the trapezius is usually a giveaway for necks and heads improperly scaled. Many animated figures (especially the older Disney characters) use a tube neck technique, where the neck is sculpted like a stovepipe from the base of the head down without tapering, and feeds into a hollow in the shoulders to torso where it is mechanically attached to the body frame. When the head turns, nods, or tilts in this model, it does so from an unnaturally low point without physical connection to the shoulders, giving a rather mechanical and unlifelike look.

We sculpt our necks to connect to the shoulders so that we can better manage scale and also so that a silicone mask has a natural attachment point to the larger torso structure against which it can move realistically, flexing and turning like real skin. At the same time, we create mechanical structures with the correct number of vertebrae to achieve realistic neck motion—it’s generally not just one point of motion to create a lifelike performance. Multiple axes increase the speed with which a figure can turn or nod its head, adding to realism, and allowing a “soupy” look that diminishes a mechanical structure’s natural inclination to look stiff. Some of GHP’s necks have up to seven individual axes of motion.

Ultimately, people’s faces are globs of flesh, fat, and muscle over a hard, structurally-sound skull. As a result, the look of a face is malleable, subject to the effects of gravity (look how different someone can look lying flat rather than standing), or to the presence of clothing or hair. If a subject is usually seen wearing a suit with a collar tight around the neck, causing a roll of flesh to appear, a portrait may look totally different and wrong with the neck looser or more svelte-looking. A natural predilection in portraiture is to flatter a subject, but this often comes at the cost of realism. In animatronics, some concessions (like a neck rubbing a collar) can be made to boost longevity in a silicone mask—loosening the collar would naturally have an effect on the flesh of the neck in the structure itself…but, is this a decision made in adjusting a sculpture at the risk of losing realism? Is it characteristic enough to matter? Sometimes, changes in costuming can make all the difference in changing the appearance of a neck, good or bad.

At the end of any neck is a skull, in portrait figures and animatronic characters most usually in the form of a fiberglass or vacuform plastic material. The underskull gives structure for the mask to rest on and, in the case of animated figures, slide over while retaining the original shape of the sculpture. As a result of shrinkage and other plastics issues, it’s easy to end up with a skull that isn’t shaped right and causes the mask to become misshapen, undermining the realism of the face. Remember, fractions of a millimeter are all it takes to significantly alter a face and make it look off model. This is particularly true of malleable skin materials designed to be moved mechanically. Striking the right balance between rigid structure and clearance for motion is key to keeping a likeness true no matter what permutations it goes through.

It all begins with the proper scaling of head and neck, and keeping those shapes inviolate. In animatronics, there is a temptation to cheat the size of a neck or head to accommodate control or power lines, or actuators. There’s a famous case of the mouth motion coil for the original 1964 New York World’s Fair Lincoln animatronic figure not fitting within the skull envelope. As a result the figure had a rather large bump on the crown of the head to accommodate the mechanical device—luckily, it was invisible to guests because it was hidden under hair.

The Animatronic Challenge

My company’s particular area of focus means almost every portrait sculpture we create will ultimately become a silicone mask on an animatronic figure. As a result, when we sculpt a face, we must pay close attention to making a specific kind of “active neutral” face. This means that a face must be at a midpoint in expression that has no specific emotion: the eyes halfway open, the mouth halfway open, eyebrows centered and even, the entire face as symmetrical in expression as possible. When it is animated, the face will want to pull to either extreme of this neutral look. If we sculpt a face favoring one of these extremes, the opposite extreme will be untenable—it won’t look real and holding it in such a pose will risk tearing a mask.

At the same time, a likeness that is meant to be animatronic can’t rely on motion to make the portrait work—the face needs to look like its subject even in the neutral state. This becomes an especial challenge when a subject character has a distinct or idiosyncratic way of moving or a particular pose unique to that individual. The successful sculpt has to look like its object in spite of changes in pose when animated, not merely because of any particular pose. Master sculptors like Blaine Gibson understood this conundrum and worked it out in interesting ways; for characters that needed a wide range, or were more “actorly,” he employed a more neutral look. For others that had specific poses that would have been difficult or impossible to achieve using animatronics from a neutral to an extreme, he sculpted them in the extreme (picture pirates playing wind instruments with puffed out cheeks and pursed lips).

Unfortunately, money is often a hindrance to going to detailed extremes in creating animatronic portraits, and certain concessions will be made to appease budget scrutineers. One I have often seen is the use of “off the shelf” or common eye mechanisms for figures. The concept is that common mechanisms have minute points of adjustment (forward and back, side to side, sometimes up and down) and can therefore be dialed in to achieve realism. But, the one size fits all concept just doesn’t work. There is too much differentiation in eye position and size to make it feasible, and, because the eyes are one of the first things people look at in both other people and in dimensional representations of them, a huge potential point for failure. The beginning of an audience’s perception of realism often begins (and can just as easily end) with the eyes.

In animating the eyes, we have found that it is easier and we have better chances of achieving lifelike realism by moving both eyes independently through their various axes (traditionally eyes have been linked and move via a single shared actuator, which causes a perceptibly mechanical look). When a person focuses their eyes on objects near or far, the eyes converge or diverge respectively. By independently moving either eye, we can replicate realistic motion along these axes. At the same time, by sculpting the eyelids as part of the intrinsic sculpture of a silicone mask, we can avoid the gaps normally caused by mechanical “trapdoor” style animation and relieve a common source of breaking the illusion of life. Eyelids also have a much greater chance of looking real if both the upper and lower lids move, allowing for both wide-eyed and squinted poses, both natural looks that may follow one right after the other in normal performance but are impossible with old-fashioned eye blinks (similarly, figures need to have their eyelids sculpted for their intended environment if they are static or only lightly animated—a figure with eyes sculpted wide open will look at home in a dark environment, but strangely out of place in bright light). An aspect we intentionally sacrifice is the corneal bulge of real eyes—in animating eyes, even this slight protrusion can be an issue, so our eyes are made totally smooth.

People are used to seeing faces move all day long in normal, daily life. Everyone we meet and interact with, see on TV, observe from afar, and see smiling in pictures informs conscious and subconscious observations about movement and detail. We read an incredible amount of expressive detail from the motion of eyebrows, cheeks, and lips. In order to create a realistic, lifelike character, we must animate the entire face, not merely the major structures. In older animatronics, only the eyes and one axis of the mouth move (an opening and closing jaw, sometimes with linked upped and lower lip curls). In GHP’s latest expressive animatronics, we move the face and eyes using more than forty unique axes of motion. The brows are critical in creating wrinkles and creases in the forehead, reflected across a wide surface from one point of motion to other stationary but reactive spots. It’s exceedingly difficult to move skin on the brow without causing unnatural bulges in one area or fake looking wrinkles in another. To achieve realistic movement, the desired wrinkling of the skin must be informed and planned in the sculpt, making motion predictable in the same way the neutral sculpt pose allows eyes to blink fully open or fully closed with equal stress on the skin.

Cheek areas move in a number of individual points—when properly animated and planned for in the sculpt, we can even achieve a remarkable crow’s feet look at the corner of the eyes. By crinkling the nose, we can create an effect across the inner cheeks, accentuated by flaring nostrils. The lips of any animated figure are the key to successful speech or singing performances. Unlike in the older figures, new characters must separate compound functions so each axis may be uniquely programmed, from jaw motion to upper and lower, inner and outer, and other lip motion (GHP’s most expressive faces have eight individual lip actuators to articulate “O,” “Eff,” and “Thhh” poses). We’ll keep our methods close to our vest, but some of our most recent figures have a totally new and remarkable capability for speaking motion, including multi-axis moving tongues.

In brows, eyes, cheeks, and lips, the speed of individual motions is critical in achieving a lifelike performance. Humanoid robots have traditionally had a relatively slow and deliberate performance across axes of motion. Using cheap, off the shelf servo motors, most figures of this type can never hope to hit complex syllabic movement in lips or the rapidity of realistic blinking. Watch yourself in the mirror and see how quickly your mouth changes shape when speaking, or what fraction of a second you can go from a happy to an angry face. Only high-end, industrial type motors can achieve the repeatable speeds necessary to really pull off a realistic performance in facial expression.

Figure Finishing and the Devil in Details

At GHP (and others who create art like us), the sculpture is only one part of the much larger process of creating a likeness. After a sculpt is finished and approved, it will be molded (tooled) and parts cast from it—sometimes in fiberglass for some static figures (like the Mayor in the well on Pirates of the Caribbean)—usually in silicone for animated or even static portrait figures. It next undergoes a series of steps to add the real essence of life, called figure finishing.

Paint is its own discipline, but in our world is really part of the figure finishing process in that it’s the first step in realizing details that help blur the line between art and technology and real life. Painting silicone skins to make them look lifelike is a unique challenge. Human skin is translucent (hold a flashlight up to your hand and you can see this, or inside your mouth to make your cheeks glow). Because of this, light is actually dispersed under the skin rather than being stopped by it. Our silicone formulations are not opaque in their liquid form, to which we add a translucent base pigmentation as the first step to color. Often, we add tiny fibers in specific areas like the nose to replicate capillaries under the skin, a technique not replicable through paint. This base is usually the darkest part of the skin, and will be added to using surface-painted yellows and blushes going from light to dark to achieve a lifelike look. Some of our most challenging work in this area has been in creating realistic prosthetics. For these, they are often immediately comparable to real skin (in the case of replacement forearms or even facial appliances). We start with a spectrophotometer to give a scientific measure to the color and light absorbency values of skin, making it easier to accurately create a painted match. It’s easy to get too translucent with paint by having too little base pigmentation (causing a washed or ghostly look) or too opaque by having too much surface paint (causing a waxy look). The balance between these and the proper application of layering is essential to achieving a realistic look.

Eyes need to be properly sized and colored for their subject and for performance realism. Although relatively close, eye sizes can vary considerably from person to person, as can iris and common pupil diameters. Eye color and iris size are critically important to the look of a figure. If irises are too dark, eyes tend to have a crazed look in contrast with the white of the eyes. Too light and they have a washed out, faded look that lacks focus. Pupils need to be sized as if reacting to the light of their performance—a character can be totally altered or muted if the pupils are too constricted or too dilated. As eyes are “the mirror of the soul,” they are frequently one of the first or the very first places people look and dwell when viewing a figure. I’ve observed over the years that one way to totally ruin the illusion of fake eyes is if they appear too flat and not moist. Eyes need a look of gloss or wetness, a shine. If mechanical eyelids make contact with the eyes, such an effect can be lost quickly, ruining the look of realism.

Eyelashes add an almost outsized sense of realism to a figure, and can do much to alter expression. They must be properly placed on the upper and lower eyelids, following closely the natural curve of the lids to the aperture. Their absence lends a strange, hollow, or even flat look to eyes. Exaggerated eyelashes draw an undue amount of attention to themselves, and can even feminize a sculpture if they are too pronounced.

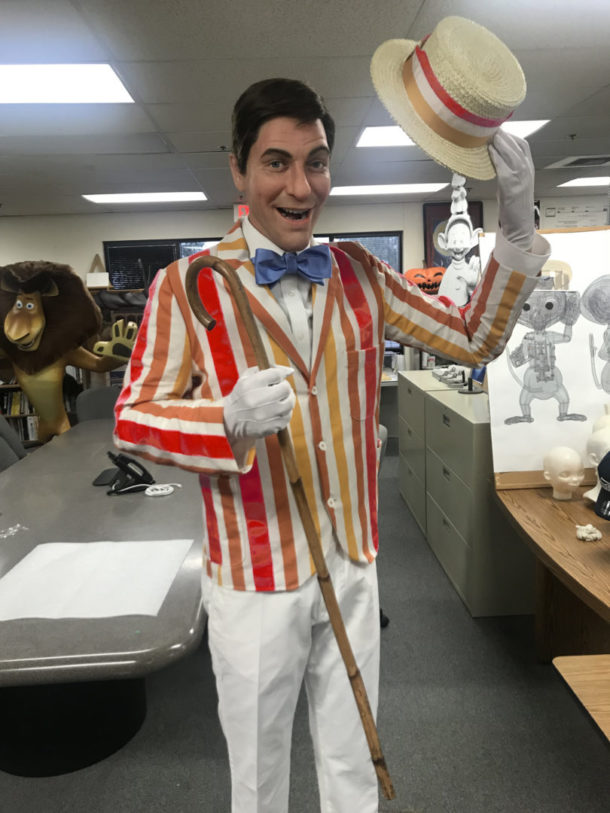

Teeth can sometimes be the linchpin holding together a successful likeness. In a smiling figure, teeth can take up a couple square inches of real estate on a face—a relatively large percentage of the whole. In some people, their teeth are so characteristic that they are as important as any other feature of the face (imagine Terry-Thomas’s famous gap, Julia Roberts’ toothy smile, or Steve Buscemi’s unusual choppers). Sometimes, off the shelf teeth or cast acrylic teeth from a common mold will do, but we frequently need to sculpt custom teeth to really capture a look. Most recently, we created custom teeth for a figure of Dick Van Dyke as Bert the chimney sweep from Mary Poppins—he has a very distinct set of teeth as characteristic as anything else in his wonderful face. The shape, color, and composition of teeth play an important structural and aesthetic role in a portrait, and should be matched to their real life counterparts, even if the reality is somewhat unflattering. The position of teeth beneath a silicone mask performs a critical function, giving body to the skin (in the same way the absence of teeth can cause the face to seem to cave in, as in some older folks with dentures removed). Upper teeth support the upper lip area and must be present and visible in a talking figure. In many cases, mechanisms push the teeth too far back from the upper lip and detract from the realism of the character.

Hair is often as varied in detail as the lines of any face. Far from being a solid helmet of any one color, hair is a palette of varying colors of differing weights and saturation. The weight of individual hairs changes as it reaches the hairline, as does the density of hair in a scalp, lending a thinning look at hairlines. Grey hair is thinner in general than colored hair. We punch hairlines (and often entire heads) using individual strands that, using a special needle tool, become embedded in the pores of the silicone mask. It’s critical when punching hair that all strands be punched in the same direction as they would on a real person’s head. The angle of insertion of each strand can affect how the sum of a full head appears. Styling hair cannot remedy mistakes in its basic directional flow, and artists must be careful to manage the angle even through tedious repetition.

Eyebrows, if not properly shaped and positioned, can cause unintended expression that can in itself seem to alter the sculptural shape of a face. Facial hair (or a lack of it) is as important as flesh structure in replicating an accurate likeness. Wig hair looks best when it’s made of real human hair. Beard hair is next to impossible to replicate accurately because of its vastly different weight and denier. As a result, GHP uses actual beard hair whenever possible in making mustaches, beards, and sideburns (this makes for some interesting stocking up!).

What It All Means

I hope you’ll excuse my lack of brevity in going through some of the pitfalls and pointers in creating accurate likenesses in animatronic or static characters. It’s a subject I think about rather frequently, and is something every theme park visitor and creator is certainly well aware of. It’s easy to get into situations where you can tell something is off about a sculpture—I hope now you know a bit more about how to remedy it. It’s often not a case of talent, or lack thereof. I remember one project we had involved an animatronic Elvis Presley. For some reason, nailing the sculpture (this was back in the days of hand-done clay sculpts) was proving a huge challenge. With each iteration, there was something just not right about the look. Ultimately, I hired three different sculptors to add their distinct touches to the face before we achieved just the right look. Each sculptor was hugely talented, but the pulling together of a dimensional portrait of a face everyone recognizes but few had dissected in all its minute detail is an amazingly arduous task.

The bottom line in undertaking any realistic portrait sculpture is: it’s HARD! It’s incredibly difficult to create an object that has the aesthetic essence of life, let alone one that must look like a particular individual person. How often have you seen a sculpture, a static, or even an animatronic figure that really looked like the person it was meant to be? Classic marble and bronze busts have a sense of “heroic stylization” to them. Even in the best wax museums, figures may look right on from certain angles, but don’t bear the scrutiny of full portraiture in the round. Sometimes, figure finishing details take on too much importance—throw a white fright wig and a mustache on practically any face in the world, and you have Albert Einstein! This is all to say that this type of art is just massively challenging and its masters are few and far between.

In looking at animated figures in the world, too, remember that oftentimes the end result has as much to do with budget as it does with the talent of the individuals working on a project. Nobody—not even Disney—has an open-ended, unlimited budget. I often hear criticisms of figures (even GHP’s own work!) commenting that, “Well, this animatronic doesn’t do a whole lot or move all that realistically—I can’t believe it’s from GHP” or “The mouths don’t even move on these Monsters, Inc. figures, they must not be very well made,” or “Look at all these miners and loggers who barely move, GHP usually does better than that!” I’d LOVE to have massive budgets for every project we have to make sure every character looks as good as it can, and moves as realistically as possible. The truth is, we almost never have budgets adequate to the task, or, perhaps more tellingly, we could have created the 50 plus figures in the Calico Mine Ride at Knott’s Berry Farm as we did with limited motion, or had one single character in there with an impressive array of expression…which would certainly be an interesting experience! That same argument says, “The house next door to mine has three more bedrooms and a marble floor in the dining room—the owner must have a better architect than me!” It’s not about the talent, it’s all about the money. When I go into a really challenging portrait sculpt, I try to set the budget to the point where I could afford to sculpt the face twice: once to get the basics in and try to land at something that works, and again to take all we learned from doing it the first time and make the final iteration perfect. Of course, this is much easier said than done! I always try to imagine that at some point, the eyes of the world will be on my company’s work, the stakes are super high, so it makes sense to put as much into making a sculpture look right as possible. After all, the things we create are designed to be seen 16 hours a day, seven days a week, all year long for many, many years.

I hope you’ll think of that the next time you see a pirate singing, a famous author joking with a founding father, or a president giving a speech!

. . . . and, no, we weren’t involved with the most recent figure added to the Hall of Presidents at Walt Disney World.

Here’s a video of our current state-of-the-art figure capable of the full range of human expressions and beyond! This demonstration shows off the figure’s animation potential, from the slightest twitch to exaggeration beyond the normal human range.

[clickToTweet tweet=”Which theme park animatronic figure do you think is the most life-like? ” quote=”Which theme park animatronic figure do you think is the most life-like? ” theme=”style3″]

You must be logged in to post a comment.