Sam is back, and this time it’s really personal. Today, we run the prologue of his new book which releases on Tuesday of this week!

Universal versus Disney: The Unofficial Guide to American Theme Parks’ Greatest Rivalry

Releases Dec 2ndPrologue

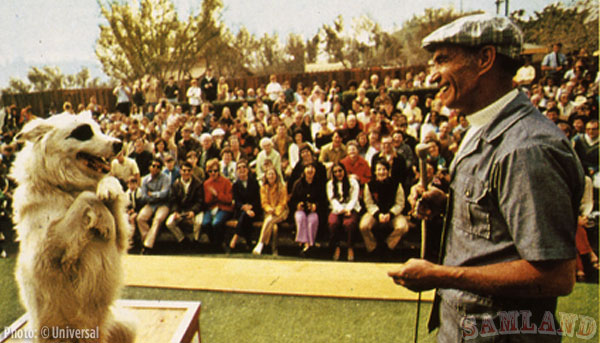

Universal Studios did not set out to challenge The Walt Disney Company in the theme park business. The men who ran the Music Corporation of America (MCA) were quite happy with the industrial tour they created in 1964 at Universal City. The Universal Studio Tour took visitors behind the scenes of the largest and busiest back lot in Hollywood to show how motion pictures and television programs were manufactured. People came from around the world with the hope of catching a glimpse of their favorite star. Unlike Disneyland, Walt Disney’s fantasy theme park in nearby Anaheim, the Universal Studio Tour provided an authentic experience not found anywhere else. It was something entirely new, entertaining, and very profitable.

In 1979 MCA bought land in Orlando 10 miles north of Walt Disney World and later announced that they were going to build a motion picture and television production studio. The new studio would have also featured a tour just like the one in California. Lew Wasserman, MCA’s legendary chief executive, knew better than to compete with Disney and its dominance with fantasy landscapes. He enjoyed the fact that the two Southern California tourist attractions complemented each other and he was making money with minimal investment.

Everything changed just a few years later. In 1984 Disney hired Michael Eisner as the new chief executive officer and Frank Wells as president. Before Disney, Eisner had been president of Paramount Pictures Corp. and Wells had been a well-respected executive at Warner Bros. Within two weeks of the Disney leadership change, MCA president and Wasserman’s protégé, Sidney Sheinberg, sent a letter to his old friends proposing a meeting to discuss ideas that would be in the mutual interest of both companies.

It made sense to turn to Michael Eisner. While he was at Paramount, Sheinberg had shown him MCA’s Florida plans with the hopes of forming a partnership. Eisner liked what he saw. When nothing came of the talks, Eisner blamed the impasse on powers higher up the corporate food chain at Paramount’s parent company, Gulf and Western. Now that Eisner was in charge of Disney, Sheinberg thought Eisner would be excited to become MCA’s partner in Florida.

During the call, a confident Sheinberg suggested to Eisner, “Let’s get together on a studio tour in Orlando. We tried with your predecessors, but they were unresponsive. We think we can help you.” Much to the surprise of the MCA executives, Eisner told his old friend, “We’re already working on something of our own.”

That was not the reaction Wasserman and Sheinberg was expecting. “Ultimately, we were informed that they might want to do one of these tours themselves and they did not want to be accused of somehow, whatever the word was, stealing or acting improperly, if we had a meeting and they later decided to go on their own,” Sheinberg later explained. “That signal really surprised us, to put it mildly. It was our first indication that they were off on a plan to do this.”

Then, on February 7, 1985, Michael Eisner made headlines at his first meeting with Walt Disney Productions shareholders. Before a packed house at the Anaheim Convention Center, he announced that Disney would soon start construction of a third theme park at Walt Disney World. The heart of Disney’s park would be a real working production studio with two sound stages and a working animation studio. Eisner said this “was a way to make the experience more authentic, but these decisions would also serve our production needs as they grew.” Regarding the plans, Eisner said they were “the most exciting to come out of Walt Disney Imagineering (WDI) in a long time.” He also told the gathering, “We’re definitely doing it within a year.”

The men at MCA were livid. After reviewing Disney’s plans, Sidney Sheinberg claimed that Michael Eisner stole the idea he heard at the 1981 pitch at Paramount. For his part, Eisner claimed the presentation occurred “many, many years” ago and added “when I arrived at [Disney], the studio tour was already on the drawing boards and had been for many years.” Eisner ordered his team to work fast. For him, beating Sidney Sheinberg and MCA was critical. “They invaded our home turf,” he told Business Week. “We will not be intimidated.”

A bitter Sheinberg replied, “You’re going to have to work awfully hard to convince me that [Eisner] didn’t know about [MCA’s plans]. That’s ridiculous. He was a member of the inner circle at Paramount.” He added, “Disney obviously felt they were in trouble and felt they had to do something about it. Disney announced it would do the theme park and would have you believe it’s been in the works since 1926—if you believe in mice, you probably believe in the Easter Bunny also.” At MCA, you do not get mad. You get even. This is how the greatest rivalry in the theme park industry began.

Sam’s collection of theme park books continues to grow. His newest book, diving into the history of Universal Studios, will release THIS week on December 2nd. Reserve your book today and Amazon will ship it out this week.

You must be logged in to post a comment.