For 12 years, Burbank had been looking for someone to build a regional shopping center on a significant piece of vacant property on Third and Magnolia, right in the heart of “Beautiful Downtown Burbank,” as comedian Johnny Carson used to say. At one point, Ernest W. Hahn Inc. had an agreement with the City to build a conventional $158 million mall, but the deal fell through. When Robert R. Bowne, a Burbank City Councilman, heard the news, he suggested, “Why don’t we let Disney dream a dream for Burbank?” That is exactly what the leadership of Burbank set out to do.

Without telling other members of the City Council, (in 1987) Councilwoman and former Mayor Mary Lou Howard contacted Michael Eisner and invited him to have lunch with her and Burbank City Manager Bud Ovrom. During the 2-hour lunch, Eisner sketched out on napkins and tablecloths some of his ideas for what to do with the property. Eisner remembered, “I was having a fabulous time. That’s what the creative process is all about.”

What could make Michael Eisner so confident that his Imagineers could create something that would be artistically and financially successful? After all, up to that time no indoor attraction had ever been really successful. For example, Fantasyland at the West Edmonton Mall in Canada barely broke the 1 million visitor per year mark at one of the largest shopping malls in the world. Later on, Disney would try to open a chain of DisneyQuest facilities with one closing very quickly (Chicago), one never making it past the foundation pouring (Philadelphia), and one limping along for many years (Orlando).

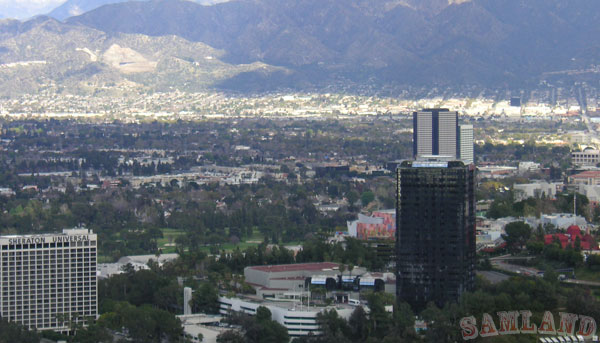

Walt Disney Productions was very interested in the concept of an indoor entertainment and retail center. For more on the political and legal battles between Disney and Universal over the Burbank Towncenter project check out my new book. For now, I want to take a look at the Southern California attractions landscape of 1987 to see why Disney thought they could find the magic formula for success.

Disney looked at all sorts of attractions. Of course, there were the theme parks like Knott’s, Universal, Sea World, Six Flags Magic Mountain, and Marineland. They also looked at other attractions such as the San Diego Zoo, the Queen Mary/Spruce Goose, Movieland Wax Museum, Medieval Times as well as Raging Waters.

One thing for certain, Southern California was a tourist Mecca. It was the second largest tourist market in the country with more than 20.5 million visitors in 1986. Not only that but within the seven county region there were more than 17 million residents. Only New York City was larger.

The Los Angeles region could boast the second largest concentration of attractions right behind central Florida. The region counted for one-third of the total theme park attendance. The biggest gorilla in the room was Disneyland with more than 36% share of the audience. At the time, Disneyland was drawing more than 12 million visitors. Plus, the visitor split at Disneyland in 1987 was 47% residents and 53% visitors. That is a far different mix then today.

Far behind Disneyland was Universal Studios, Knott’s Berry Farm, San Diego Zoo, Sea World and Magic Mountain. Attendance for those attractions ranged from 3 to 4 million annually. Marineland closed in 1987. Raging Waters and Medieval Times were new and looked very promising. All of this was big business. Revenues topped $700 million in 1986. Disneyland took home the lion share capturing 47% of the total money spent.

There was a dark cloud on the horizon. Changing demographics and how people used their leisure time were threats to the attractions industry. The population was getting older and families were having fewer children. Is a theme park still relevant to an older person? Could Disney take advantage of this trend in Burbank?

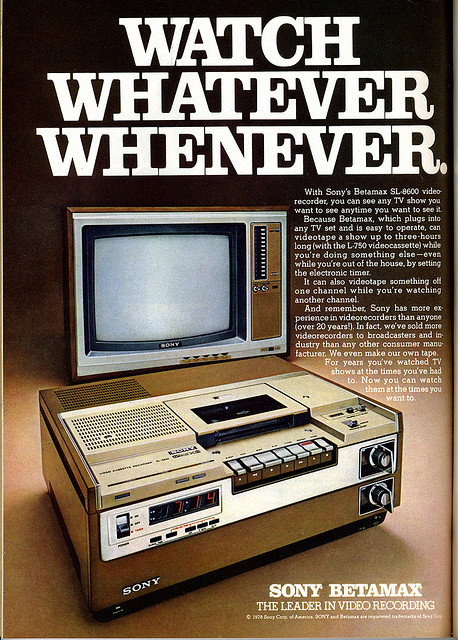

Another trend that was talked about at great length during the mid-1980s was “Cocooning.” It was a time when people had new entertainment technology options available that allowed them to stay home. Video cassettes, home computers, video games, and cable television anchored people onto their sofas.

Plus, the attractions business was starting to become saturated. Expectations had changed. People no longer wanted to be passive spectators. They wanted to actively experience something. This was a time when Medieval Times and plays like Tamara were gaining in popularity. This was also a time when going to Club Med was a lifestyle statement.

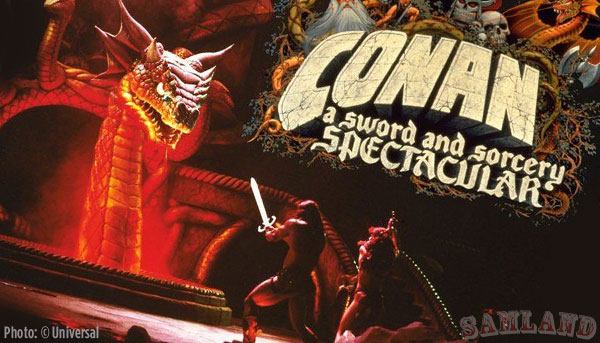

To generate demand, the theme parks were reinvesting a lot of money. Universal Studios had budgeted $75 million to building an 18-screen movie complex, the Adventures of Conan show, King Kong, Miami Vice, and the Castle Dracula show. Sea World added 19 acres with Muscle Beach, a new Whale tank and a new children’s area. Knott’s was also growing. They added $10 million worth of new attractions in 1987. The family friendly Kingdom of the Dinosaurs, a new 3D theater show, and rehab of Fiesta Village were meant to drive attendance.

Competition for the theme park dollar was fierce. New competitors included water parks (Raging Waters), children’s parks such as Camp Snoopy at Knott’s, and the aforementioned interactive shows. Remember playing War Tag or Photon?

So what about Burbank? Did building a Disney themed indoor entertainment center seem like a sure thing? Not if one took a look at the landscape. How many remember visiting Old Chicago, Autoworld, The World of Sid and Marty Kroft, and the Baltimore Power Plant? Generally, indoor attractions of this sort are too expensive to build, too expensive to maintain, too expensive to update, and more likely than not to underwhelm the visitors. After a visit to Disneyland, how can you compete?

For Disney, building an indoor entertainment/retail center in Burbank meant coming up with a plan that did not scream “Disneyland.” There was no way they were going to compete with the theme park. Instead, the idea was to target people who might visit a entertainment retail center say at Universal City. Remember, this was before CityWalk opened.

Would it have worked? Push the politics and business dealings aside and my answer is probably not. What do you think?

Sam’s collection of theme park books continues to grow. His newest book, diving into the history of Universal Studios, was just released on December 2nd. Pick up your copy today. They make great Christmas gifts!

You must be logged in to post a comment.